How Time Zones Work

Written by: Ceyda Storme

Many people might assume there are 24 time zones in the world—one for each hour of the day. It sounds logical, but that kind of thinking doesn't always work in the world of time zones. Depending on how you count them, there may be more than 40, including those offset by half or even quarter hours. And how the time zone map is drawn today may be useless tomorrow. Oh, and there are 26 hours in a single day, at least according to time zone math, in case you didn't know.

Welcome to the world of time zones, a fascinating mix of science, geography, and politics. In this article, we’ll break down everything you never wanted to know about time zones, including a few fun facts about how the world keeps time.

What a Time Zone Is

A time zone is a region of the Earth that shares a uniform standard time for political, economic, and social purposes. It’s a practical invention that synchronizes clocks across an area so that everyone runs on the same schedule. In essence, a time zone is a compromise between aligning the clock with the Sun—so that noon is roughly when the Sun is at its highest—and the human need for order in day-to-day life.

How Time Zones Are Measured

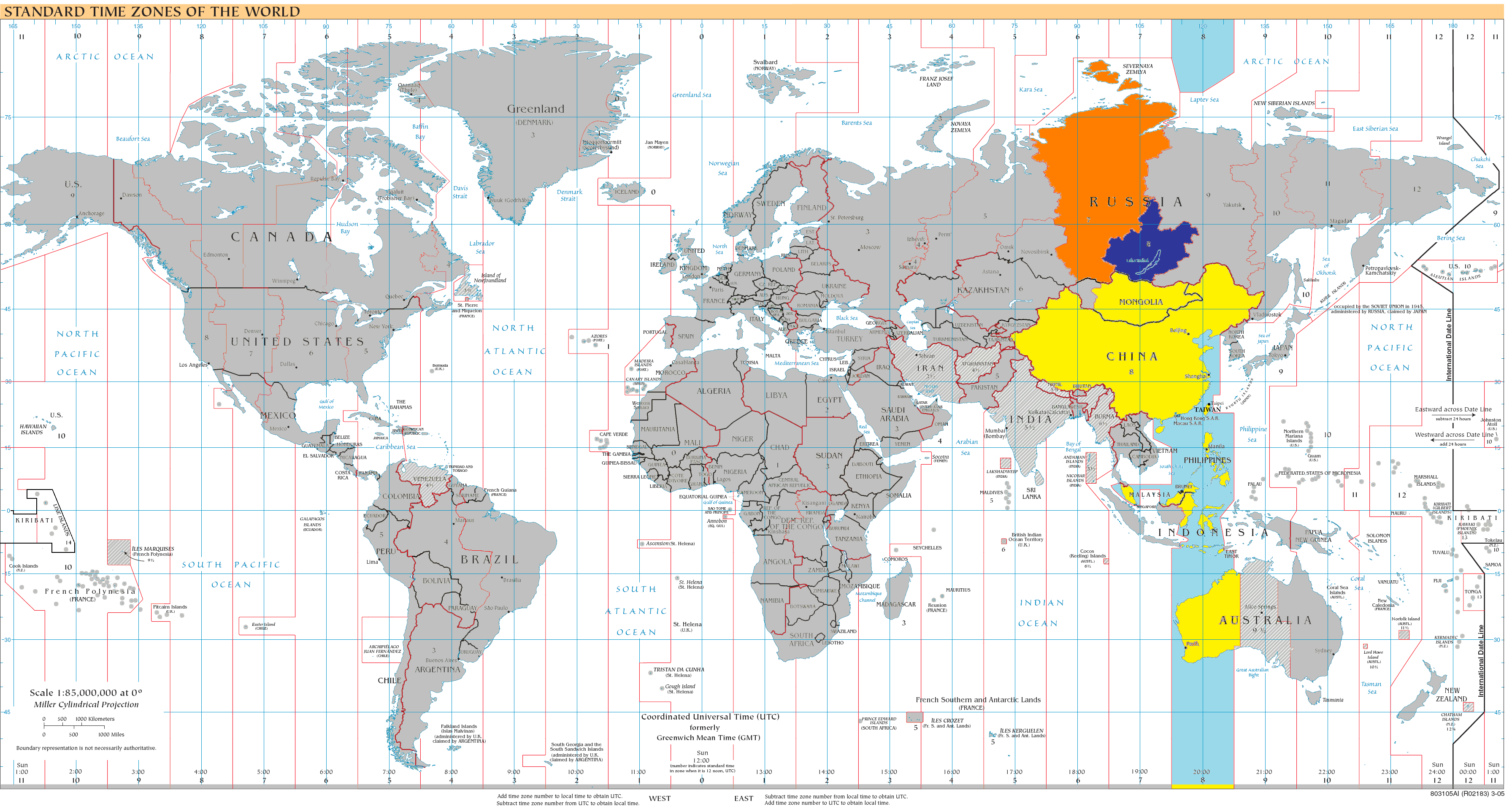

Time zones are measured by their distance from a universal starting point. Today, that starting point is "UTC +0", or zero hours from Coordinated Universal Time (abbreviated as UTC). UTC is not a time zone, it is a time standard from which all time zones are derived. It is, in many ways, the world time standard.

UTC +0 (or simply "UTC") runs along the Prime Meridian, which is the line of longitude at 0°. Geographically, this line passes through Greenwich, London, in the United Kingdom, which is significant because UTC is what ultimately replaced GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) as the ruler by which time zones are measured.

The further east you travel from UTC +0, the greater the offset becomes, and thus the more time zones you pass through. For example, if you traveled eastward from London to Warsaw, you would end up in UTC +1—one hour ahead of UTC. And therefore, if you traveled westward, to New York City, for example, you would end up in UTC -5—five hours behind UTC.

Time zones of the world (UTC)—UnaitxuGV, Heitordp and others, public domain, source

Time zones of the world (UTC)—UnaitxuGV, Heitordp and others, public domain, sourceHowever, depending on what time of the year this was, and which country you actually travelled to, these numbers would likely change, because of Daylight Savings Time, which we will get to later.

A Quick History of Time Zones

Before time zones, each town kept its own local solar time, determined by the position of the Sun overhead. Noon in one city might be several minutes earlier or later than in another just a few miles away. This worked fine when travel and communication was slow, but the rise of railways and telegraphs in the 19th century turned things on their head. Train schedules became nearly impossible to coordinate, and even simple telegraph messages were difficult to manage.

To solve this, railway companies in North America took the lead in pushing for standardized time. They wanted a unified system for all trains, wherever they were, so that every route could be run safely and on schedule. Among those who recognized the need for a global solution was Sir Sandford Fleming, a Canadian railway engineer who proposed dividing the world into twenty-four time zones. His ideas lead to the International Meridian Conference of 1884, which officially established the foundation of the modern time zone system.

UTC

Before UTC, GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) was the official time standard. The problem with GMT was that it relied on the rotation of the Earth to make its calculations, which made it irregular, since the Earth's rotational speed is irregular. By the 1950s, it had become evident that GMT lacked the precision required for rapidly advancing technologies—including navigation, radio communication, and early satellite systems. Something new was needed.

And that something new would arrive in 1955, when Louis Essen and Jack Parry built the first practical atomic clock, accurate to about one second in 300 years, a revolutionary leap at the time. And it was not long after the invention of the atomic clock that UTC emerged, a system built on precision, pushed by a coalition of scientific and international timekeeping organizations eager to use this new technology.

More than sixty years later, UTC is still the global time standard today. UTC has since evolved and is now anchored to International Atomic Time (TAI), a highly stable time scale derived from a weighted average of hundreds of atomic clocks around the world. UTC, however, still needs to be synchronized with the Earth's position (solar time) so that, for instance, midnight still occurs near the time the Prime Meridian faces away from the Sun. The result is a time standard that keeps civil time in near-perfect sync with the stars in the night sky.

You may be wondering why UTC is not abbreviated CUT. The acronym UTC was chosen as a compromise between the English name, Coordinated Universal Time (which would be CUT), and the French name, Temps Universel Coordonné (which would be TUC). Selecting UTC avoided favoring any single language for the global standard.

Time Zone Tally

The days of twenty-four time zones are long gone. A once relatively simple system is now a complex one, one that is constantly changing. It's become so complex, in fact, that even knowing how many time zones there are today is no simple task. Ask three people how many time zones there in the world and you might get three different answers. And this is largely because there is no single authority that dictates them.

The way it works in reality is that each sovereign country sets its own time zones based on its own set of rules, rules that are often shaped by political, economic, and practical considerations. These rules often override the neat 15-degree longitudinal divisions that once divided the globe into 24 one-hour time zones.

When measured by actual time differences used worldwide, most experts recognize between 37 and 40 unique UTC offsets—or "time zones". The reason that there can be more than 24 is because not every country follows whole-hour increments. Many use half-hour or even quarter-hour differences. India and Iran, for example, use half-hour increments—UTC +5:30 and UTC +3:30, respectively. And Nepal and Australia’s Central Western Time, for example, use quarter-hour increments—UTC +5:45 and UTC +8:45, respectively.

The other reason there can be more than 24 time zones is because the range of potential offsets is larger than you might expect. And this is where things really get weird. The world’s time zones span from UTC −12 to UTC +14, a full 26-hour range. You read that right, 26 hours in a day. This means that when it’s midnight on one side of the globe, it’s already the next evening on the other.

The Eventium Calculator, to use an example, recognizes 38 distinct time zones as part of its milestone calculations. This number, however, could have very easily been slightly more or slightly less, depending on how the developers defined their rules for counting.

Time Zone Politics

What may not come as a surprise is that politics is largely what has complicated the time zone system. Because there is no international body that oversees the division of time zones, and because countries will prioritize national unity and convenience over geographical accuracy, the time zone map has its share of oddities.

For example, China is geographically vast, spanning over 3,000 miles (4,800 km) from east to west, which would naturally put it in five different geographical time zones. However, the entire country officially observes one time zone, Beijing Time (UTC +8). The result is extreme time disparity: in the western provinces like Xinjiang, the Sun may not rise until nearly 10:00 AM in the winter, and solar noon (when the Sun is at its highest) can be as late as 3:00 PM local time. This single zone is largely used as a political tool to promote a sense of national unity centered around the capital.

UTC +8—MrMingsz, public domain, source

UTC +8—MrMingsz, public domain, sourceBecause of political decisions like China's single time zone, crossing certain international borders can result in massive, non-standard time jumps. Crossing the border from China (UTC +8) to Afghanistan (UTC +4:30), you would have to set your clock back by 3 hours and 30 minutes.

In 2015, North Korea moved its time zone back by 30 minutes to create a new time zone called Pyongyang Time (UTC +8:30). The official reason was to mark the 70th anniversary of the liberation from Japanese rule. Three years later, in 2018, North Korea moved its clocks back to UTC +9, in alignment with South Korea, in advance of a historic summit between the two nations, which was seen as a gesture intended to promote unity and reconciliation.

In the Pacific, the island nation of Kiribati realigned its side of the International Date Line, making its easternmost islands the first place on Earth to start the new day (UTC +14). This means a tiny hop from its neighbor American Samoa (UTC −11) results in a 25-hour time difference!

The time zone at UTC +14 is the earliest on Earth, meaning it’s always the "next day" there. Conversely, UTC −12 is the latest, so some islands experience a day almost 26 hours behind others. That’s why you can have "tomorrow" and "yesterday" happening simultaneously!

And despite being physically smaller than the U.S. or Russia, France has the highest number of time zones of any country: 12. This is because the count includes all of France's overseas departments and territories scattered across the globe, from the Caribbean (like Martinique) to the Pacific Ocean (like French Polynesia). Russia and the United States only come in second, with 11 time zones each.

Daylight Savings Time

As if a world of independently defined time zones wasn't complicated enough, Daylight Saving Time (DST) takes it to another level. Adopted by some countries and ignored by many others, DST is the ritual—usually twice a year, every year—of rocking the clock forward and backward by one hour, like someone who can't make up their mind.

DST is not always twice a year every year, among the countries that observe it, anyway. A few countries, like Morocco, have chosen to permanently adopt their DST offset year-round, essentially giving themselves a new, non-standard time zone. But the "spring forward, fall back" model is the one that is still most commonly used throughout the world today.

One of the most interesting aspects of DST is that nobody knows officially why it exists. The reason that is most often cited is energy conservation. The claim is that by extending the window of sunlight into the evening for a portion of the year, total energy consumption is reduced. This reason makes the assumption that people won't simply use that saved-up energy in the morning, which is now one hour earlier and one hour darker. And they apparently do, which may explain why some studies that measure energy consumption during DST are inconclusive.

Whether DST was created for economic gains or social gains is unknown. What is certain, however, is that the majority of the world does not observe it. It may sound strange to someone who has never lived in a part of the world that does not observe DST, but it's true: there are places in the world you can live today that never change their clocks. Much of Africa and Asia remain on the same time year-round, and even within countries that do use DST, large regions choose to opt out entirely. For billions of people, the concept of "springing forward" or "falling back" simply isn’t part of daily life. Doesn't sound so bad, does it?

Anything but Standard

Time zones may seem like a simple concept—a way to keep the world’s clocks in sync—but as you’ve seen, they’re anything but simple. What began as a logical system rooted in astronomy has evolved into a global patchwork shaped by politics, economics, and human convenience. And when we add the complexities of Daylight Saving Time to an already tangled system, we see that even the measurement of something as universal as time is still subject to debate, culture, and circumstance.

Yet despite the irregularities, it all works—mostly. Planes still take off and land when they're supposed to (usually), financial markets still open and close on schedule, and people around the world still manage to meet at the right hour (give or take a few minutes). In the end, time zones are a perfect reminder that our concept of time isn’t just scientific—it’s human. It’s an invention we’ve collectively agreed to follow, one that balances precision with practicality in a world that never truly stands still.